When a Healing Herb Is Not What It Claims to Be

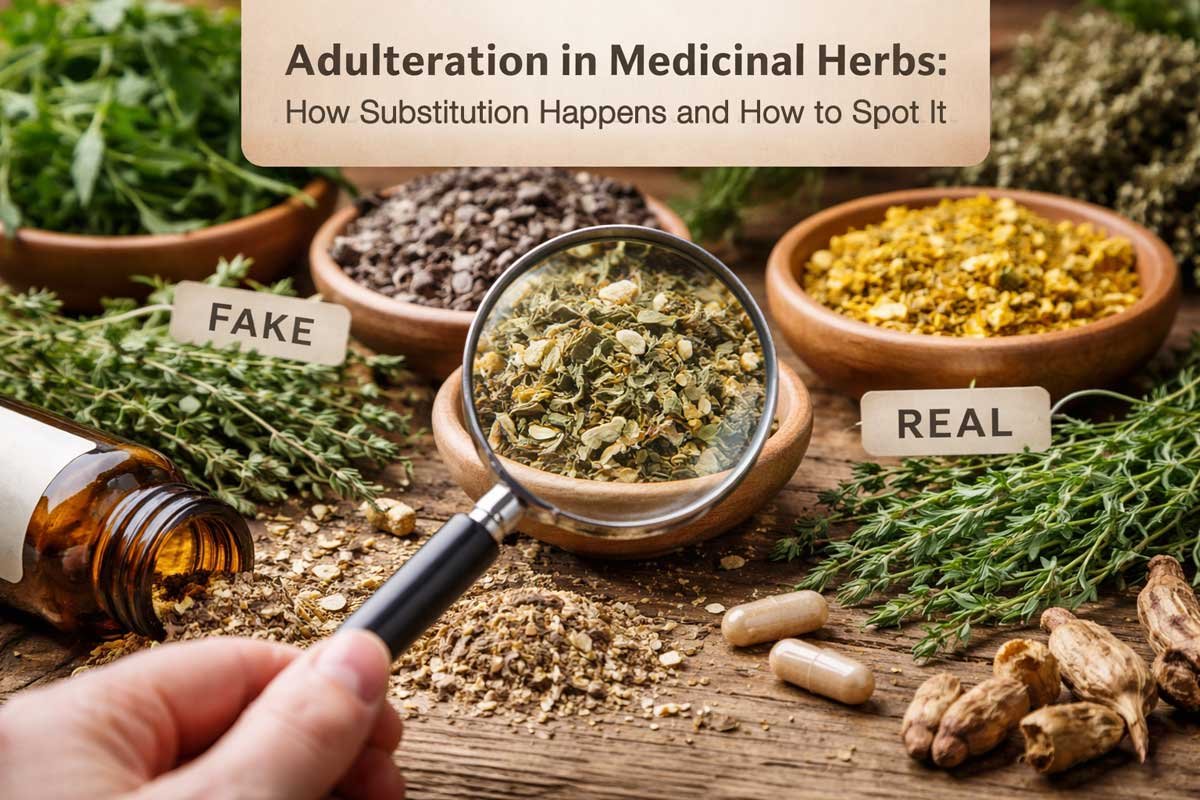

Walk into any herbal shop, and the shelves are lined with vibrant jars, colorful packets, and neatly stacked bottles. Each promises wellness, balance, and a natural path to health. Yet behind the appealing labels and earthy fragrances, there’s a hidden truth that most consumers rarely see: not every herb is exactly what it claims to be. Adulteration—when a medicinal herb is partially or entirely substituted with another plant or substance—has quietly plagued herbal markets for centuries. Even today, despite regulations, laboratory tests, and organic certifications, the risk remains real. Understanding how and why this happens is the first step toward protecting yourself and your herbal practice.

Adulteration is not always malicious. In some cases, it occurs because of honest mistakes: misidentification of species in the field, confusion during processing, or contamination during storage. However, economic pressure is a constant driver. High-demand herbs can fetch premium prices, and when supplies are limited due to seasonal variation, overharvesting, or geopolitical restrictions, sellers sometimes turn to substitutes—either plant species that look similar or fillers that bulk up weight. In powdered forms, where visual or tactile verification is impossible, these substitutions become especially easy to conceal.

Table of Contents

Consider ginseng, one of the most widely sought-after medicinal herbs. Wild ginseng, known for its adaptogenic properties, is scarce and highly valuable. Unscrupulous sellers sometimes mix lesser-known Panax species or even unrelated roots into ginseng powders. The difference is not just academic: chemical analyses reveal variations in active compound levels, which can significantly affect the herb’s therapeutic profile. While an occasional substitution might not cause harm, consistent adulteration undermines the integrity of the herb market and erodes consumer trust.

The problem is compounded by the globalization of herbal supply chains. Many herbs sold in Western markets originate thousands of miles away, harvested in remote regions with minimal oversight. Herbs travel through multiple intermediaries—collectors, processors, exporters, and distributors—before they reach consumers. At each stage, there is a potential for error or intentional substitution. Even with regulatory frameworks in place, enforcement is uneven. Field collection often occurs in rural areas with little infrastructure, where workers may not be trained to distinguish between similar species. Processing plants, particularly those producing powdered herbs or capsule blends, may not invest in rigorous testing. Once these herbs reach the shelf, the original source is often obscured, making traceability difficult.

Another factor contributing to adulteration is the complex morphology of herbs. Many medicinal plants have look-alike species, sometimes referred to as “adulterants” in the literature, that are visually similar to the intended herb but chemically distinct. For example, black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) has been substituted with cheaper Asian counterparts, leading to variability in chemical profiles. Some substitutions are outright toxic, while others simply reduce efficacy. Even experienced herbalists can struggle to identify these differences without laboratory tools like DNA barcoding or chromatography, which are not standard practice in many markets.

The powdered form of herbs is especially vulnerable. Once a leaf, root, or bark is crushed and packaged, most visual clues vanish. Color, texture, and smell can provide hints, but these sensory methods are limited and subjective. Filler substances—starch, powdered grains, or unrelated plant fibers—can be blended in without detection. Chemical analysis can detect some forms of adulteration, but testing every batch is costly and rarely feasible for small producers or importers. For consumers, this creates a paradox: even when buying “organic” or certified products, absolute assurance of authenticity is challenging.

Organic certification adds another layer of complexity. While certification indicates adherence to specific farming practices—no synthetic pesticides, sustainable cultivation, and traceable supply chains—it does not automatically guarantee that the herb is free from substitution. Certification agencies focus primarily on production methods rather than detailed species verification. Consequently, adulteration can occur even under certified labels, particularly in high-volume products sourced from multiple farms. This gap between certification and absolute authenticity has fueled research into advanced testing methods, including DNA barcoding and metabolomic profiling, which can identify mislabeling down to the species level.

Economic incentives for adulteration are significant. Some herbs are endangered or protected, creating scarcity that drives substitution. Others are simply costly due to demand outstripping supply. Consider saffron, the world’s most expensive spice. In its medicinal context, saffron is sometimes replaced with marigold petals or dyed materials in powdered form to increase profits. While saffron adulteration is well-documented, similar patterns exist across herbal markets—from turmeric and ginseng to black cohosh and echinacea. In each case, the financial benefit for the supplier can outweigh the perceived risk, particularly when testing is minimal and enforcement weak.

Consumers are not helpless, though. Awareness is the first tool against adulteration. Learning to recognize reputable suppliers, understanding the provenance of the herb, and demanding transparency at each step can reduce risk. Sensory evaluation—looking at the color, texture, and aroma of the herb—remains useful for whole herbs but is less effective for powders or extracts. Independent lab testing, though expensive, provides a definitive method for confirming identity. Increasingly, companies are using QR codes, batch numbers, and supply chain mapping to give consumers more confidence. Still, the reality is that substitution can occur even with the best intentions, which is why vigilance is essential.

The consequences of adulteration extend beyond economic loss. Variability in chemical composition can lead to inconsistent results for users relying on herbs for wellness purposes. In worst-case scenarios, toxicity or adverse reactions occur when a substituted herb contains compounds that interact with medications or affect vulnerable organ systems. Even when harm is unlikely, the principle of authenticity matters: if you pay for ginseng, you want ginseng, not a look-alike root. Trust in the herb market hinges on the integrity of the supply chain, and adulteration undermines that trust.

Adulteration is a multifaceted problem, shaped by economic, botanical, and logistical factors. It exists at the intersection of human behavior, natural variability, and regulatory limitations. Herbs are living organisms, grown in diverse environments, harvested by people with varying levels of expertise, and processed in facilities with different quality controls. Every step presents opportunities for substitution, intentional or accidental. While laboratory science is increasingly capable of detecting these issues, the challenge is systemic, requiring transparency, vigilance, and education for both suppliers and consumers.

In practice, spotting adulteration requires a combination of knowledge, intuition, and skepticism. Familiarity with the herb’s typical morphology, aroma, and color can help, but it is rarely sufficient for powders or extracts. Understanding the market, supply chain, and certification standards is critical. Asking questions about sourcing, requesting documentation, and favoring suppliers who provide transparency are proactive measures. Awareness of the issue itself creates a lens through which all purchases can be evaluated more critically.

Adulteration in medicinal herbs is not just a historical relic; it is an ongoing concern that impacts trust, efficacy, and safety. Recognizing that a seemingly simple herb may not be exactly what it claims to be is the first step in navigating the complex world of herbal products. Awareness, scrutiny, and careful sourcing are the tools that allow consumers to make informed decisions. As the demand for natural remedies continues to grow, so does the responsibility to ensure that what reaches your shelf—or your hand—is genuinely what it purports to be.

How Adulteration Enters the Medicinal Herb Supply Chain

The journey from a plant growing in a field to a dried herb in your cabinet is far from simple. Each step—harvest, processing, transport, and storage—creates opportunities for adulteration, whether intentional or accidental. Understanding how these risks accumulate in the supply chain reveals why even “organic” or high-quality medicinal herbs can end up compromised.

Economic Pressure and Scarcity of Raw Materials

Economic incentives are perhaps the most significant drivers of adulteration. Popular herbs such as ginseng, echinacea, or black cohosh can fetch high prices, creating a strong temptation to stretch limited supplies. Scarcity often arises from overharvesting, environmental changes, or regulatory restrictions designed to protect endangered species. When demand exceeds available supply, suppliers may turn to cheaper alternatives or fillers to meet quotas.

Even when an herb is grown organically, scarcity can push intermediaries to source from multiple farms, sometimes in entirely different regions. Each additional source increases variability and the risk of substitution. For example, wild ginseng harvested in North America may be mixed with cultivated Panax species from Asia. While these roots look similar, their chemical profiles differ, and only laboratory analysis can reliably detect the substitution. In this way, economic pressure can compromise authenticity at the very first stage of the supply chain.

Intentional Substitution Versus Accidental Mix-Ups

Adulteration can be deliberate or accidental. Intentional substitution occurs when a supplier knowingly replaces a high-value herb with a cheaper species or filler to maximize profit. This is common in powdered herbs, where visual inspection is impossible, and consumers have little way to detect deception. Even dried leaf or root can be substituted if the species is visually similar.

Accidental mix-ups are equally important to consider. Herbs are often harvested and stored in bulk, sometimes alongside unrelated plants with similar appearances. Workers may misidentify species, particularly in regions where multiple herbs grow together. In large-scale operations, such errors can propagate through the supply chain before they are detected, effectively creating unintentional adulteration. Both forms—intentional and accidental—pose risks to the quality, efficacy, and safety of medicinal herbs.

Misidentification at Harvest and Early Processing

The earliest stages of the supply chain—harvest and initial processing—are particularly vulnerable to misidentification. Many medicinal herbs have look-alike species that are morphologically similar but chemically distinct. Black cohosh, for example, is frequently confused with cheaper Asian Actaea species. Without proper training, harvesters may collect the wrong plants, which then enter the supply chain as genuine medicinal herbs.

Processing introduces additional risks. Leaves, roots, and barks are washed, cut, dried, and sometimes powdered. During these steps, parts of the plant may be mixed incorrectly, or foreign material may contaminate the batch. In some regions, inadequate labeling and handling procedures allow multiple species to be combined inadvertently. These early errors, compounded by insufficient oversight, can make their way to the final product, sometimes without anyone realizing the substitution occurred.

Powdered Herbs and the Loss of Visual Verification

Powdered and finely processed herbs are especially prone to adulteration. Once an herb is crushed, most visual and tactile cues vanish, making it nearly impossible to detect substitution with the naked eye. Fillers such as starch, powdered grains, or unrelated plant material can be blended in without noticeable changes in color or texture. Even small amounts of adulterants can alter the chemical profile of the herb, reducing potency or introducing unintended compounds.

This loss of visual verification also complicates quality control. Laboratory testing can identify substitutions, but testing every batch is expensive and often impractical for suppliers, particularly small-scale producers or importers. Consumers are therefore left relying on supplier reputation, certification, and traceability systems, which, while helpful, cannot guarantee absolute authenticity. The risk is not hypothetical; numerous studies have shown widespread substitution in powdered herbal products, including ginseng, black cohosh, and echinacea, highlighting the limitations of visual inspection alone.

Common Forms of Adulteration in Medicinal Herbs

Medicinal herbs are celebrated for their natural compounds, diverse health-supportive properties, and historical use across cultures. Yet, the reality is that these herbs are often compromised before they ever reach consumers. Adulteration manifests in several distinct ways, each with its own risks and mechanisms. Understanding these common forms is crucial for anyone navigating the herbal market.

Species Substitution and Look-Alike Plants

Species substitution is one of the most prevalent types of adulteration. Here, one plant species is replaced with another—either intentionally or accidentally—often because the substitute is cheaper, more abundant, or visually similar. For example, black cohosh (Actaea racemosa), widely used for hormonal support, is sometimes substituted with cheaper Asian Actaea species that look almost identical. While these look-alikes may share some chemical characteristics, critical compounds may differ in concentration or be absent entirely.

Misidentification is particularly common with roots and leaves that are dried or processed. Even experienced collectors can struggle to differentiate between species in certain stages of growth. This form of adulteration is not merely cosmetic; it can influence the efficacy of herbal remedies. DNA barcoding studies have repeatedly revealed that commercially sold “authentic” herbal products often contain substitute species, demonstrating that visual inspection alone is insufficient to guarantee authenticity.

Use of Fillers, Dyes, and Inert Materials

Another widespread form of adulteration involves the addition of fillers or inert substances to increase weight or volume. Common fillers include powdered grains, starches, or cellulose fibers, which are often undetectable in powdered forms. These materials do not provide the intended herbal compounds, effectively diluting the product.

Dyes are occasionally added to enhance color and make the herb appear fresher or more potent than it actually is. For instance, turmeric powders may be dyed to look more vibrant, or ginseng roots may be artificially colored to resemble high-quality wild specimens. While these additions may seem harmless, they mislead consumers and compromise the overall integrity of the herb. Even small amounts of fillers or dyes can reduce the concentration of active compounds, making the herb less effective and undermining trust in herbal products.

Synthetic Additives Disguised as Natural Compounds

A more insidious form of adulteration is the inclusion of synthetic compounds disguised as natural constituents. Some manufacturers add synthetic analogs of active herbal compounds to boost potency or mimic effects. These chemicals are often not disclosed on labels, and in some cases, they can interact with medications or pose health risks.

For example, studies have found instances where powdered herbal supplements contained synthetic flavonoids or alkaloids to simulate the expected therapeutic profile. Consumers may believe they are getting a fully natural product, but in reality, they are ingesting a chemical additive. Detecting such adulteration requires specialized laboratory analysis, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or mass spectrometry, tools that are rarely accessible to individual buyers. This form of adulteration is particularly concerning because it combines economic deception with potential safety issues.

Geographic Origin Fraud and Label Manipulation

Geographic origin fraud occurs when herbs are falsely labeled to suggest they come from a specific region known for high-quality production. Herbs grown in less desirable or lower-quality regions may be marketed as premium products from renowned locations, misleading consumers. For example, ginseng labeled as “wild American” may in fact be cultivated in Asia, or saffron sold as originating from Iran may come from lower-grade sources elsewhere.

Label manipulation extends beyond geography. Claims such as “organic,” “wildcrafted,” or “ethically sourced” can be misused when proper certification is lacking or verification is incomplete. Even when certification exists, the link between the farm and final product may be obscured by complex supply chains, creating opportunities for fraud. Geographic and labeling adulteration undermines transparency, making it difficult for consumers to assess quality, trustworthiness, and value.

Organic Status, Testing, and the Limits of Trust

When buying medicinal herbs, the term “organic” often carries a sense of reassurance. Labels suggest purity, careful farming, and a lower likelihood of contamination. Yet, the reality is more nuanced. While organic certification addresses certain quality factors, it does not guarantee freedom from adulteration. Understanding the strengths and limitations of certification, testing, and sensory evaluation is essential for anyone relying on medicinal herbs.

Does Organic Certification Reduce Adulteration Risk

Organic certification primarily confirms adherence to farming and handling practices: avoidance of synthetic pesticides, responsible soil management, and traceable cultivation. Certification can reduce the risk of contamination with chemicals, but it is not a foolproof safeguard against species substitution or other forms of adulteration.

The certification process rarely involves detailed species verification. Inspectors may check cultivation practices, soil conditions, and harvest methods, but they typically do not perform DNA testing or chemical profiling on every batch of herbs. As a result, an herb labeled “organic” may still be substituted with a cheaper or unrelated species. Organic certification reduces certain risks, such as chemical residues, but does not eliminate the possibility of adulteration. It is one piece of a larger strategy for ensuring herbal quality.

Where Lab Testing Helps and Where It Falls Short

Laboratory testing can detect many forms of adulteration, providing a scientific basis for authenticity claims. Techniques such as DNA barcoding, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and mass spectrometry can identify species, detect synthetic additives, and measure active compound concentrations. Studies have repeatedly shown that commercial herbal products often contain species not listed on the label, underscoring the value of lab verification.

However, lab testing has limits. It is costly and time-consuming, making it impractical to test every batch of a product, especially for small-scale suppliers. Tests can confirm the presence of a specific compound or species but may not detect fillers, dyes, or geographic origin fraud unless specifically targeted. Moreover, testing provides a snapshot of one batch and does not guarantee that subsequent batches maintain the same standard. For consumers, this means that lab-verified authenticity is valuable but not absolute, highlighting the importance of multiple quality control strategies.

Sensory Clues and Practical Red Flags for Buyers

Despite advances in science, traditional sensory evaluation remains an important tool. Experienced buyers can assess whole herbs for color, aroma, texture, and general appearance, detecting inconsistencies that may signal adulteration. Powdered herbs are more challenging, but subtle cues—such as unusual color intensity, clumping, or an atypical scent—can suggest the presence of fillers or dyes.

Practical red flags include unusually low prices, unclear sourcing information, inconsistent labeling, or products sold by suppliers with limited transparency. If a herb is rare or in high demand, an exceptionally cheap product should prompt caution. Asking questions about the origin, harvest practices, and handling of the herb, and requesting certificates or testing results, can help identify trustworthy sources. Combining sensory awareness with inquiry and documentation provides a practical defense against adulteration.

Transparency, Traceability, and Supplier Accountability

Ultimately, the ability to trust an herbal product depends on the transparency of the supply chain. Traceability measures—batch numbers, QR codes, supplier documentation, and detailed sourcing information—allow both suppliers and consumers to track herbs from field to shelf. Companies that provide this level of accountability are less likely to engage in or tolerate adulteration.

Supplier accountability also involves consistent testing, clear labeling, and open communication with buyers. Even with organic certification and lab testing, the most reliable protection against adulteration comes from suppliers committed to rigorous standards and transparent practices. When choosing medicinal herbs, prioritizing traceable sources, verified organic farms, and reputable distributors significantly reduces risk, even though no single measure guarantees complete protection.

Learning to Read Between the Labels

Buying medicinal herbs can feel like navigating a maze. Labels promise purity, organic status, or ethical sourcing, but in reality, these claims often only tell part of the story. Learning to read between the labels isn’t about becoming a lab scientist overnight—it’s about developing awareness, asking the right questions, and spotting patterns that hint at quality or hidden risks.

The first step is understanding what labels actually represent. Terms like “organic,” “wildcrafted,” or “ethically sourced” are regulated differently depending on the certifying body or country. Organic certification focuses on cultivation methods rather than confirming the exact species or purity of a herb. Wildcrafted herbs indicate that plants were harvested from natural habitats, but this doesn’t automatically rule out misidentification or substitution. Even a label touting traceability can be misleading if the supply chain is complex and opaque. Recognizing these limits helps set realistic expectations and prevents blind trust.

Next, pay attention to sourcing details. A label that specifies country of origin, farm name, or batch number is usually a sign of transparency. Herbs that simply claim “imported” or list a generic region offer little accountability. High-demand herbs like ginseng, black cohosh, or saffron are particularly vulnerable to substitution or geographic fraud. Understanding where your herb comes from allows you to cross-check availability, seasonality, and reputation of the supplier. If something doesn’t add up, it’s worth investigating before purchasing.

Price can also be a subtle but reliable indicator. While affordability is appealing, a price that is too low for a rare or high-quality herb often signals adulteration or dilution. Powdered or processed herbs that seem unusually cheap are especially suspect. Cost alone isn’t proof of authenticity or adulteration, but when combined with other red flags—unclear sourcing, missing certification, or unusual appearance—it becomes a strong cue to scrutinize the product more closely.

Sensory inspection remains surprisingly effective. Whole herbs offer visual cues: roots should feel firm, leaves retain characteristic colors and textures, and stems shouldn’t crumble unnaturally. Aromas can also reveal inconsistencies; a medicinal herb that smells bland or chemically altered may have been adulterated or improperly stored. Powdered herbs are trickier, but clumping, uneven color, or an unusual scent can hint at fillers, dyes, or substitution. Developing a familiarity with each herb over time sharpens this intuitive sense, allowing you to catch inconsistencies that might escape labels and certifications.

Finally, combine labels with verification tools and questions. Ask suppliers about testing protocols, batch analysis, and traceability measures. Look for companies willing to provide documentation or lab results on demand. QR codes, batch numbers, or supply chain maps are more than marketing—they are practical evidence of accountability. When combined with organic certification, transparent sourcing, and sensory awareness, these tools create a multi-layered defense against adulteration.

Reading between the labels is ultimately about cultivating informed skepticism. No single certificate, claim, or inspection guarantees authenticity, but by integrating multiple approaches, you reduce risk significantly. Over time, this approach becomes second nature: a quick glance at the label, a sense of provenance, and subtle sensory checks tell you more than the printed claims alone. In a market where adulteration is common, the informed buyer has the power to navigate complexity, choose wisely, and ensure that the medicinal herbs purchased truly reflect what they promise.

Best-selling Organic Products

Article Sources

At AncientHerbsWisdom, our content relies on reputable sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to substantiate the information presented in our articles. Our primary objective is to ensure our content is thoroughly fact-checked, maintaining a commitment to accuracy, reliability, and trustworthiness.

- World Health Organization. (2007). WHO guidelines for assessing quality of herbal medicines with reference to contaminants and residues. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43510

- World Health Organization. (2011). Quality control methods for herbal materials. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44479

- Booker, A., Johnston, D., & Heinrich, M. (2012). The adulteration of herbal medicines: a review of causes, consequences, and detection methods. Drug Safety, 35(8), 631–647. https://doi.org/10.2165/11631770-000000000-00000

- Ichim, M. C. (2019). The DNA-based authentication of commercial herbal products reveals their globally widespread adulteration. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 10, 1227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01227

- Newmaster, S. G., Grguric, M., Shanmughanandhan, D., Ramalingam, S., & Ragupathy, S. (2013). DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Medicine, 11, 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-222

- Posadzki, P., Watson, L., & Ernst, E. (2013). Adverse effects of herbal medicines: an overview of systematic reviews. Clinical Medicine, 13(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.13-1-7

- Sangiovanni, E., Brivio, P., Dell’Agli, M., & Calabrese, F. (2017). Botanicals as modulators of neuroplasticity: focus on BDNF. Neural Plasticity, 2017, 5965371. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5965371

- Nectarine: Stone Fruit for Heart Health and Antioxidants - March 8, 2026

- Peach: Hydrating Fruit for Skin Health and Digestion - March 8, 2026

- Plum: Fiber-Rich Fruit for Digestion and Heart Health - March 8, 2026