The Story of Bai Zhi Root

Bai Zhi Root, also known as Angelica dahurica, has been a fixture in Traditional Chinese Medicine for well over a thousand years. If you were to wander into an old apothecary in Beijing, past drawers lined with fragrant dried herbs, you’d almost certainly find Bai Zhi tucked into one of them. The smell is sharp and earthy, slightly sweet but with a nose-tingling bite that reminds you of freshly dug roots mixed with spice.

This isn’t a trendy new “superfood.” It’s one of the old reliables, a root that physicians from the Han dynasty onward leaned on for headaches, sinus congestion, and stubborn infections. Its name literally translates as “white angelica,” a nod to both the pale color of the root and its family ties to the angelica genus.

And here’s the thing: when you brew it into a decoction or grind it into a powder, it doesn’t just carry history with it—it carries a punch. The kind of relief you can feel right in your sinuses or temples after just a few sips.

Table of Contents

What Makes Bai Zhi Root Special

At first glance, Bai Zhi might look like any other dried root: beige slices, a little fibrous, a little brittle. But dig into the plant chemistry, and you’ll see why it has earned its place.

- Coumarins: Bai Zhi is rich in compounds like imperatorin and isoimperatorin, which have been shown to reduce inflammation and fight microbes.

- Volatile oils: These give the root its aromatic kick and contribute to its decongestant qualities.

- Polysaccharides: Supporting immune function and helping the body push out lingering infections.

It’s this combination—warming, dispersing, antimicrobial—that makes it such a versatile herb.

Traditional Uses in Chinese Medicine

Ask a traditional practitioner how Bai Zhi is used, and you’ll hear about its affinity for the lungs, stomach, and bladder meridians. The language might sound foreign at first, but in practice it points to very specific and relatable effects.

- Relieving sinus congestion: Bai Zhi helps clear wind-cold type headaches, often the kind where your forehead feels like a heavy block of stone and your nose just won’t stop running.

- Easing pain: Especially frontal headaches, toothaches, and orbital pain around the eyes.

- Expelling pus: It’s been classically prescribed for boils, abscesses, or lingering infections where the body needs a nudge to discharge what’s stuck.

- Warming the body: Not in a hot pepper way, but in a subtle, circulation-boosting way that drives out chills and dampness.

There’s a saying in some circles that Bai Zhi clears the “gates of the head.” It sounds poetic, but anyone who’s dealt with sinus pressure that makes even blinking hurt knows exactly what that means.

Sinus Support and Headache Relief

If you’ve ever reached for a decongestant spray during allergy season or when a cold blocks up your face, you’ll appreciate Bai Zhi’s power. Decoctions made with Bai Zhi root work almost like a gentle natural vapor rub. The root helps open nasal passages, reduce swelling in the mucous membranes, and promote freer breathing.

Headaches, especially those that sit right above the eyebrows or radiate across the forehead, are where Bai Zhi shines. Instead of dulling pain like over-the-counter pills, it works to correct the underlying imbalance—improving circulation, reducing inflammation, and releasing the stuck energy that often shows up as pounding pain.

Pain Beyond the Head

Bai Zhi doesn’t stop at sinuses. It’s also used for:

- Toothache: Applied as a poultice or included in a decoction. The root’s antimicrobial properties help reduce infection, while its analgesic effects ease the throbbing.

- Joint pain: Particularly when it’s aggravated by damp, cold weather. Think of that heavy, achy stiffness that creeps into the knees or lower back when it rains.

- Menstrual pain: While not its primary indication, Bai Zhi sometimes finds its way into formulas aimed at warming the uterus and easing cramps.

Modern Research on Bai Zhi Root

Traditional use is one thing, but modern science has also been digging into what Bai Zhi can actually do. Researchers have noted several interesting effects:

- Anti-inflammatory activity: Coumarins isolated from Bai Zhi show measurable reductions in swelling and inflammatory markers in lab studies.

- Antibacterial and antifungal: Extracts inhibit common pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans.

- Analgesic potential: Studies suggest Bai Zhi compounds act on the nervous system to reduce pain sensitivity, aligning neatly with its headache-relieving reputation.

- Antioxidant properties: Protecting cells from oxidative stress, which may help explain why it’s often used to promote skin healing in traditional contexts.

Of course, research is ongoing, and much of it is still in early stages. But the overlap between old knowledge and new findings is hard to ignore.

How Bai Zhi Root is Prepared

If you walked into a Chinese herbal shop, you’d likely see Bai Zhi sliced into thin chips. From there, it can be used in several ways:

- Decoction: Simmered with other herbs for about 20–30 minutes, creating a warm, earthy tea.

- Powder: Ground and taken directly, or mixed into pills.

- Topical: Sometimes applied in pastes for boils, skin infections, or toothache.

- Essential oil: Rare, but distilled Bai Zhi oil has been used in aromatherapy and external applications.

It’s rarely used alone in traditional practice. Instead, it’s paired with herbs like Xin Yi Hua (magnolia flower) for sinus congestion, or Fang Feng for headaches. The synergy matters.

Safety and Precautions

Like any powerful herb, Bai Zhi root isn’t for everyone.

- Pregnancy: Traditionally avoided, as it may stimulate uterine contractions.

- Allergies: Those sensitive to plants in the Apiaceae family (celery, parsley, carrot) should be cautious.

- Overuse: Large doses can cause nausea, dizziness, or dry mouth.

The general approach is simple: use with respect, preferably guided by someone who knows the herb well.

A Few Personal Notes

I’ve always thought of Bai Zhi as the “unclogger.” You know that feeling when your head is so stuffed it feels like cotton has been jammed into every sinus cavity? A hot decoction of Bai Zhi can cut through that fog in ways few herbs can.

There was one winter where I battled an endless cycle of sinus infections. Antibiotics helped, but they left me drained. A practitioner gave me a blend heavy in Bai Zhi, and the difference was night and day. The pressure eased, the headaches softened, and I felt like I could finally breathe again.

And honestly, isn’t that what most of us are after? To breathe fully, to move without pain, to feel like our bodies aren’t dragging us down?

Key Takeaways

- Bai Zhi Root is a classic Chinese herb used for sinus relief, headaches, and pain.

- Its active compounds include coumarins, volatile oils, and polysaccharides.

- Traditional uses focus on dispersing wind, clearing congestion, and reducing pain.

- Modern research supports its anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and analgesic properties.

- Safe use requires caution, especially in pregnancy or with allergies.

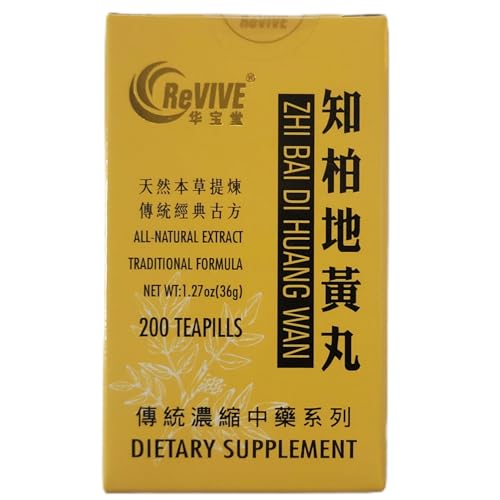

Best Selling Bai Zhi Supplements

Final Thoughts

Bai Zhi Root doesn’t dazzle with exotic color or trendy branding. It doesn’t need to. It’s been quietly doing its work for centuries: clearing noses, soothing pain, and helping people find relief in the middle of daily life.

When you sip it as part of a warm decoction, you’re not just taking in plant chemistry—you’re tapping into a lineage of healing that stretches back through generations. And sometimes, that old wisdom really does hold up under the light of modern science.

Article Sources

At AncientHerbsWisdom, our content relies on reputable sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to substantiate the information presented in our articles. Our primary objective is to ensure our content is thoroughly fact-checked, maintaining a commitment to accuracy, reliability, and trustworthiness.

- Chen, J., & Chen, T. (2004). Chinese medical herbology and pharmacology. Art of Medicine Press.

- Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy. (2002). Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (English Edition). Chemical Industry Press.

- Jiang, J., Jiang, J., & Wang, C. (2015). Phytochemical and pharmacological profiles of Angelica dahurica: A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 160, 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.11.039

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2022). Angelica dahurica. PubChem. Retrieved from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Angelica-dahurica

- Pan, Y., Kong, L., & Zhang, Y. (2016). Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of imperatorin from Angelica dahurica. Phytotherapy Research, 30(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5492

- World Health Organization. (1999). WHO monographs on selected medicinal plants: Volume 1. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42052

- Zhou, J., Xie, G., & Yan, X. (2011). Encyclopedia of traditional Chinese medicines: Molecular structures, pharmacological activities, natural sources and applications. Springer.

- Plant-Based Iron, Iodine, and Mineral Support Using Herbs - January 23, 2026

- Vegan Alternatives to Beeswax and Honey in Herbal Preparations - January 22, 2026

- Alcohol Free Herbal Extracts, Glycerites, Vinegar Extracts, and Teas Explained - January 22, 2026